A town ahead of its time

The beginnings of industrialization in the nineteenth century have several economic and social consequences. In Europe and North America several cities emerge, organised in function of industrial production. Born out of industrial society’s specific needs, urban planning or town planning gradually emerges worldwide as a new discipline and occupation. A masterpiece of the human creative genius, the town of Arvida marks a turning point in the history of industrialization and socio-industrial utopias. It represents the culmination of decades of research on workers' housing, new towns and planned industrial cities.

The Hygienist Movement

In Europe, the history of health and the history of urban planning are closely linked. As early as the eighteenth century, doctors consider cities to be responsible for numerous diseases. The layout of cities, the crowding and proximity of people and animals, as well as poor hygiene, result in an unsanitary urban environment. This gives rise to the idea that cities must be changed in order to benefit from clean air. This recognition, in the nineteenth century, gives rise to hygiene awareness, and thus to the transformation of urban spaces.

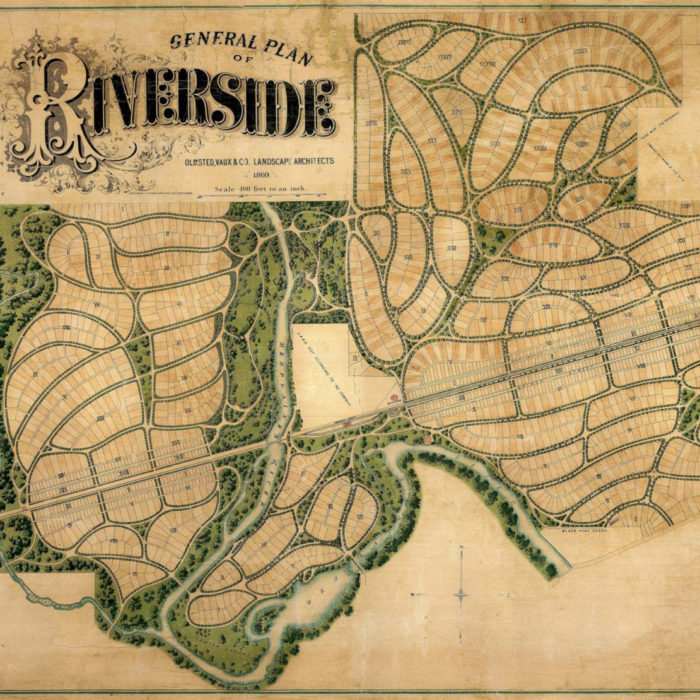

Biologist and sociologist, Patrick Geddes adopts the idea that there is a close link between the environment and its inhabitants. For him, the development of cities must be planned according to social as well as environmental aspects. Accordingly, Geddes recommends incorporating nature in the city. In the same vein, Frederick Law Olmsted, an American landscape architect, advocates the conservation of natural elements to create green spaces.

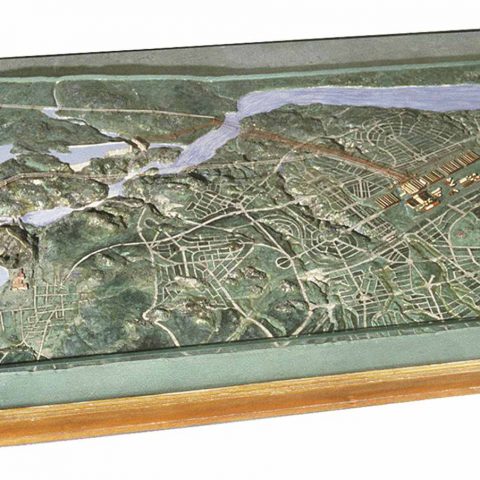

The importance of keeping green spaces was taken in account as the plans for Arvida were made. For this reason, the layout of the streets and parcels follows the topography, leaving room for the gully behind the schools, notably.

City Beautiful

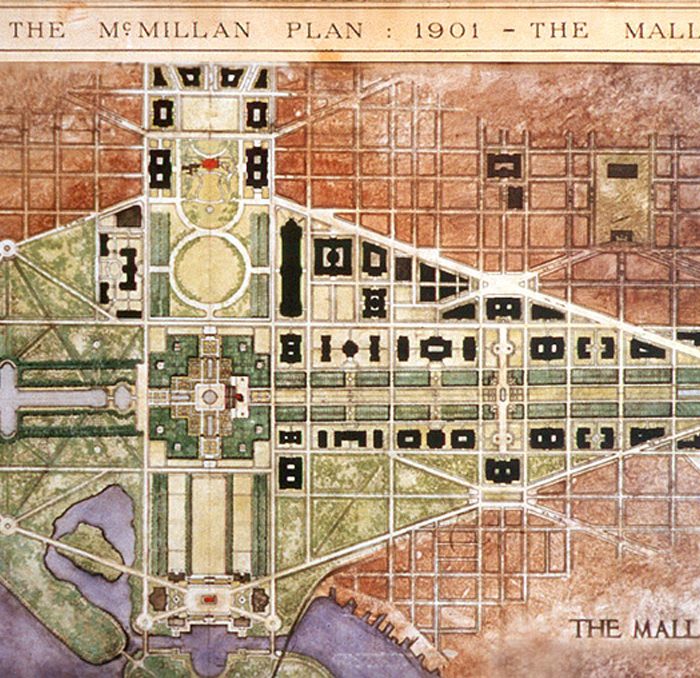

In the early 20th century, the city is seen as one of the means to improve the conditions of the community. An architectural and urban movement called City Beautiful develops, with the goal of beautifying cities. Very influential in North America, the movement is closely linked to the plans for the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair, as elaborated by Frederick Law Olmsted. The latter proposed to create a green frame made of parks connected to one another by walkways on banks and avenues, called the Park System.

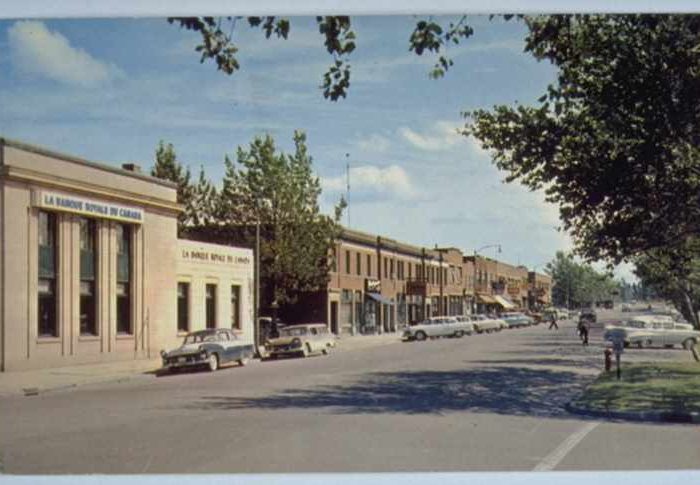

City Beautiful emphasizes the integration of a city centre, parks and wide boulevards. The shops are close to each other, insuring a constant flow of people. In order to preserve the attractiveness of this central area, means of transport are facilitated. Zoning rules are essential to establish some measure of control. The City Beautiful movement intends for the city centre to reflect the city’s dynamism, its progress and its prosperity. It aims to offer residents an impressive urban landscape whose balance and harmony of neoclassical and baroque architecture ensure its beauty.

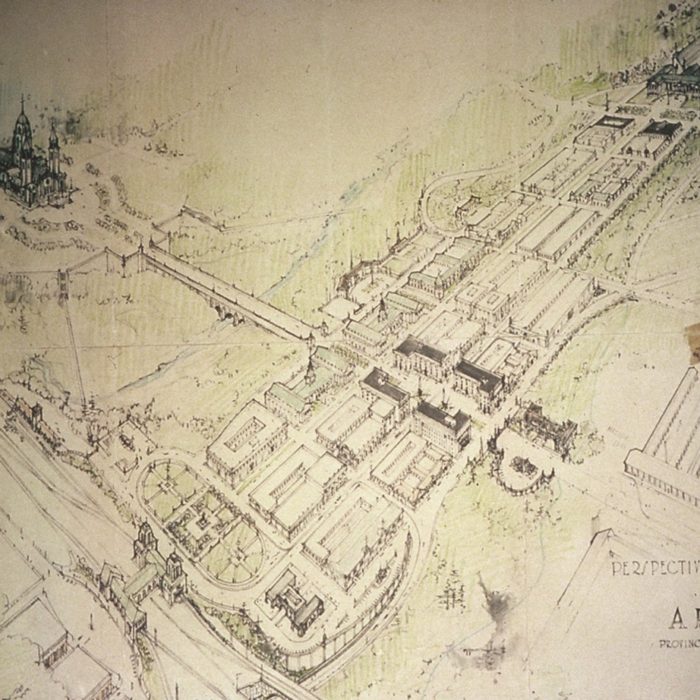

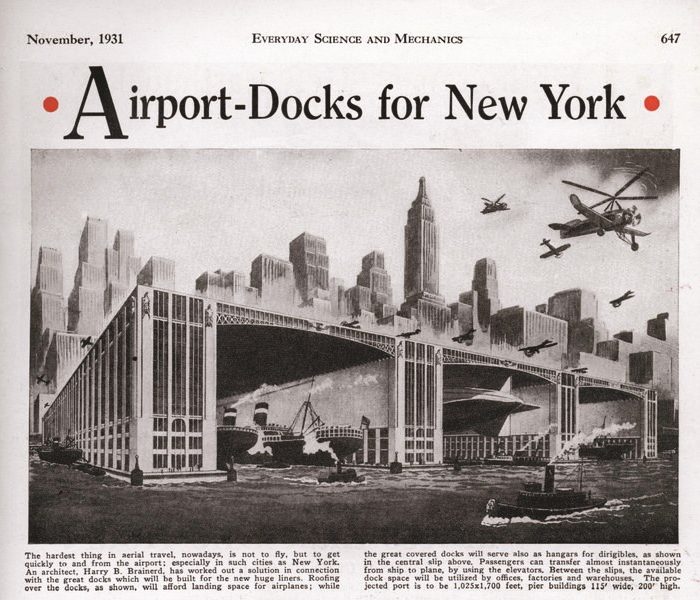

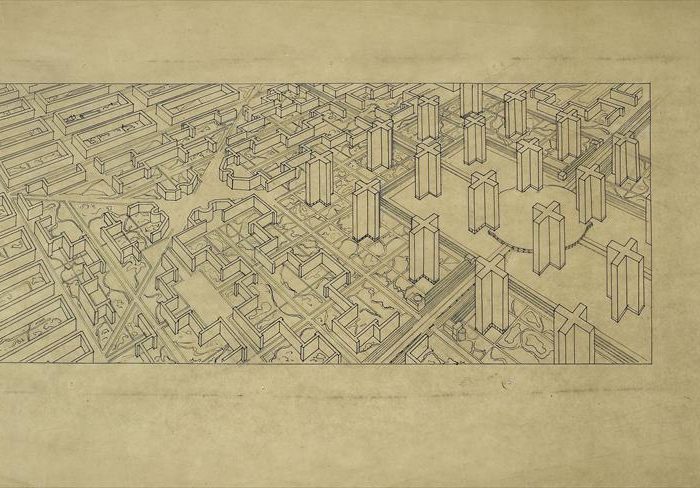

The City Beautiful movement was very influential, particularly for cities like Cleveland, Chicago and Washington. Establishing itself in the region, Alcoa wants to make Arvida an aluminum metropolis. Consequently, the city is influenced by this movement. The plan, Perspective of Business District: Town of Arvida, attributed to Brainerd, presents an imposing city centre linking a cathedral on one side with the factory on the other, as well as a civic centre and a railway station. There are wide avenues surrounded by gardens and lined with symmetrical, classically-inspired buildings. Furthermore, downtown Arvida is built according to regulations. Buildings must not be higher than the width of a street, and must be clad in brick or stone. The point is to ensure a certain level of homogeneity.

Garden City

Industrial development during the nineteenth century, particularly in England, leads to a variety of social upheavals, including an increase in the urban population to the detriment of the countryside. Rapidly, cities become overcrowded, causing disastrous sanitation and living conditions. Thus rises an anti-urban mood. Facing the horrors of the city, citizens see a refuge in nature.

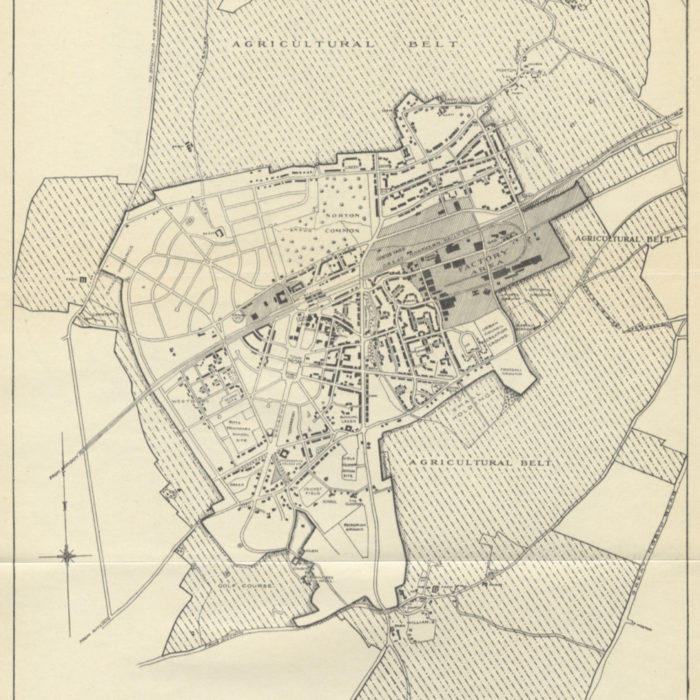

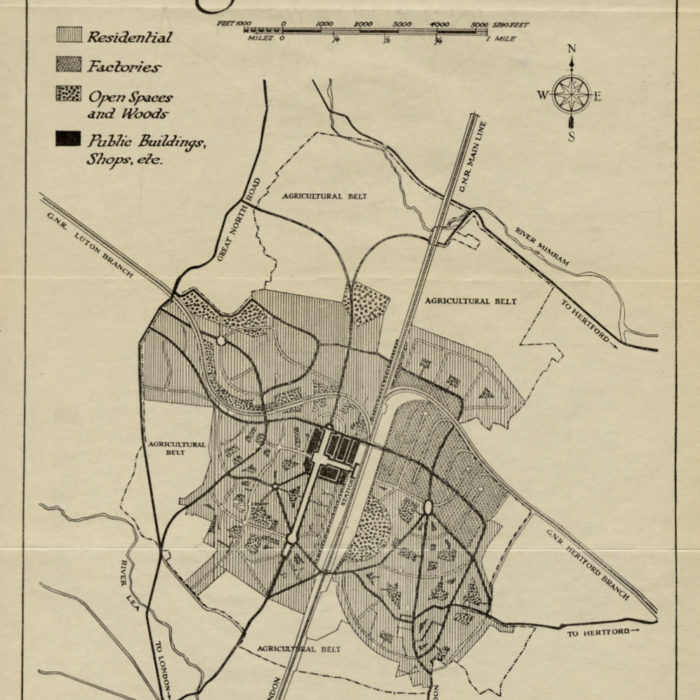

It is in this context that the British urban planner Ebenezer Howard publishes a book entitled To-morrow: A Peaceful Path to Real Reform. The theory he develops proposes creating a hybrid place, a combination of urban and rural, where the advantages of both are found. This is the principle of the Garden City, represented in his “three magnets” diagram. Howard’s ideal city is a small town of 6,000 acres (2,400 hectares) with a population limited to about 30,000. The city is completely independent, managed and financed by its citizens, as well as being self-sufficient thanks to the agricultural belt bordering the city. Howard’s concept is carried out with the creation of Letchworth Garden City and Welwyn Garden City, both located in England.

In Canada, Thomas Adams is the promoter of the Garden City concept, introducing several Canadian designers to the movement. First secretary of the Garden Cities Association, he establishes the Town Planning Institute of Canada and produces the plans for the first planned Canadian cities of the twentieth century, including Témiscaming.

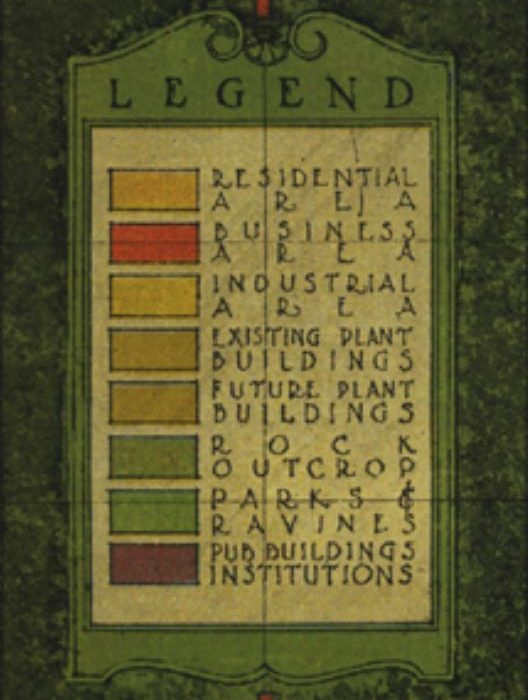

Being the town of the Aluminum Company of Canada, Arvida is unique. Designed to be attractive and comfortable, it is an ideal place to live and raise a family. There are no hovels or slums, and the landscaping is a primary feature. Parks, groves and ravines contribute to the town’s charm and beauty. As early as 1927, the company plants over 700 trees, including 158 elms, 467 poplars, 51 willows and 33 silver maples. The inhabitants also participate to the embellishment of the town by prettifying their lawn, notably with flowers and gardens. In this town, nature holds a central place.

Functionalism and the Charter of Athens

The disorderly development of cities leads urban planners and architects to redefine the way they are built. It is at the 4th International Congress of Modern Architecture (CIAM) that they establish a program for the planning and construction of cities based on four main functions: housing, work, transport and recreation. The Charter of Athens, organised and subsequently published by Le Corbusier, is a summary of the main points addressed at the congress.

Among the many points defining functionalism, one finds the principle of zoning, which is essential to allocate space according to the four functions. Sunshine, greenery and open spaces are central to functionalism. Thus, the French architect and urban planner Le Corbusier favours keeping tall buildings at a certain distance from each other, leaving open spaces and taking advantage of the sunshine. Thus, green spaces become available for recreational use. Industries should not be located too far from residences to limit transportation. Le Corbusier, the researcher who established the principles of functionalism, is the authority to numerous urban planners in the 1950s and 1960s.

The aluminum city is designed according to a functional sectorization which divides the town into green spaces, residential neighbourhoods and the institutional downtown sector. The residential, leisure and institutional areas are separated and distinct from the mill’s industrial site, which makes Arvida a town ahead of its time in urban planning history. The neighborhood centre (roundabout) facing Sainte-Thérèse-de-l’Enfant-Jésus Church separates the various functions, such as habitation, circulation, work and leisure. This type of urban planning is an early form of functionalism, the practical applications of which would appear later.

The creators

The planning and construction of Arvida is the result of the decisive influence of several key players.

Edwin Stanton Fickes

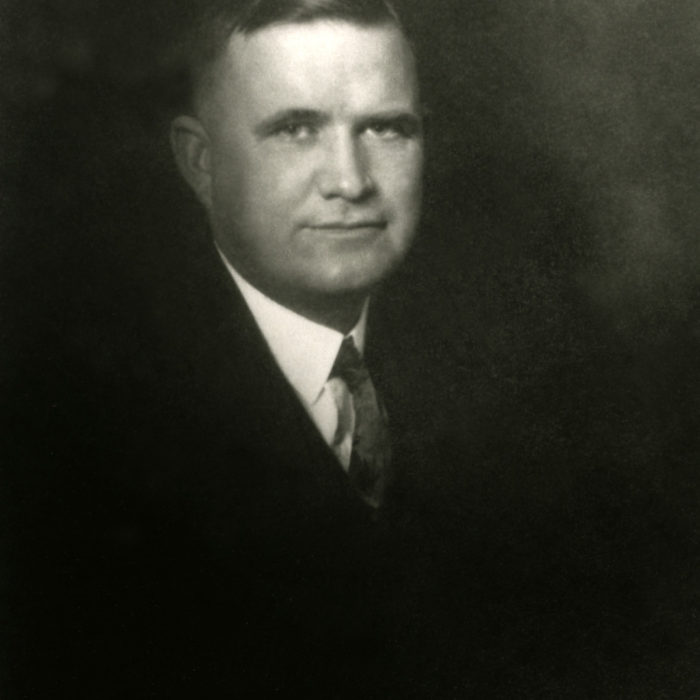

Edwin Stanton Fickes, a graduate of the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in New York, works in New York for five years before being recruited by Alcoa to carry out the plans for the Shawinigan aluminum smelter and to oversee its construction.

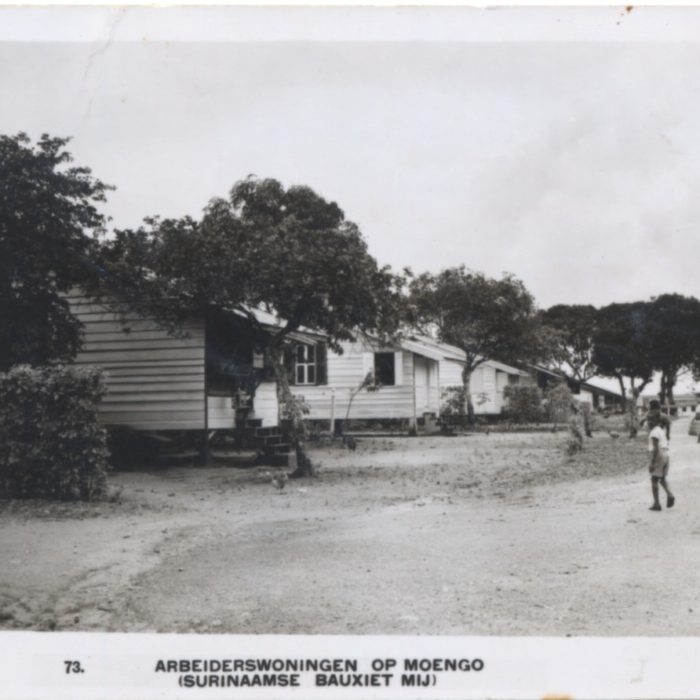

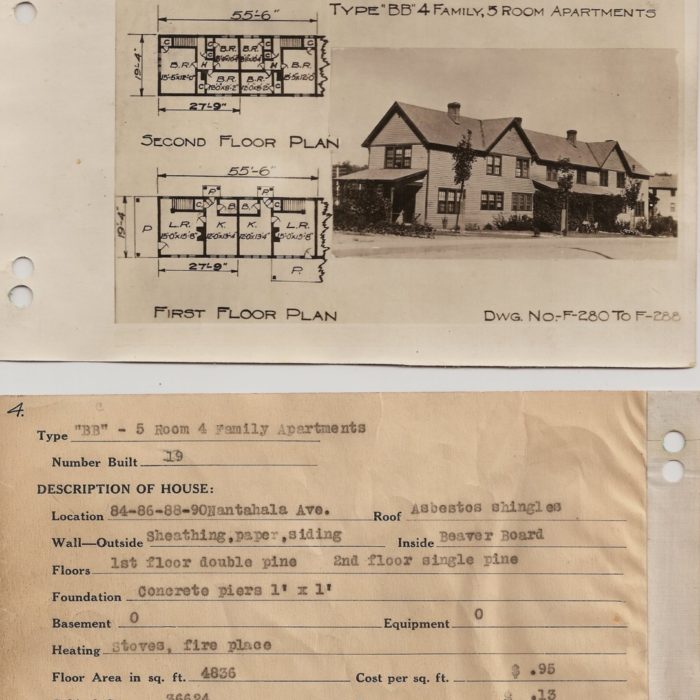

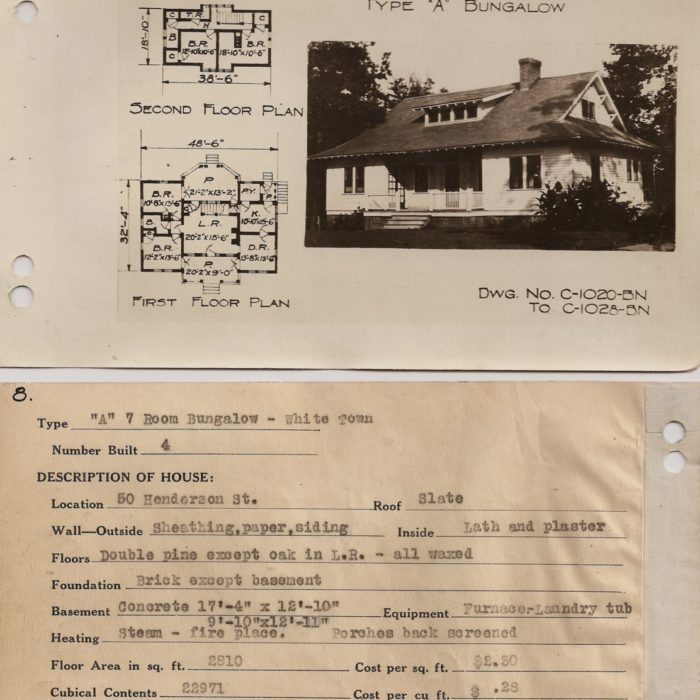

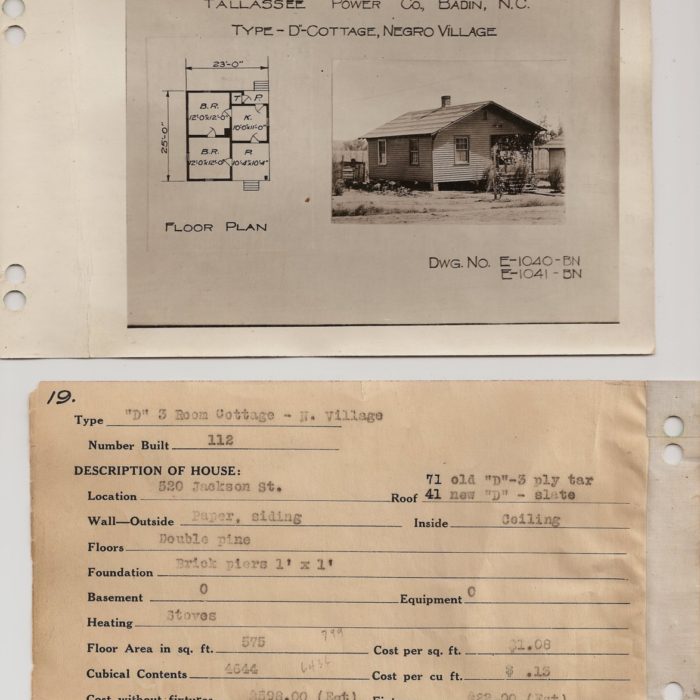

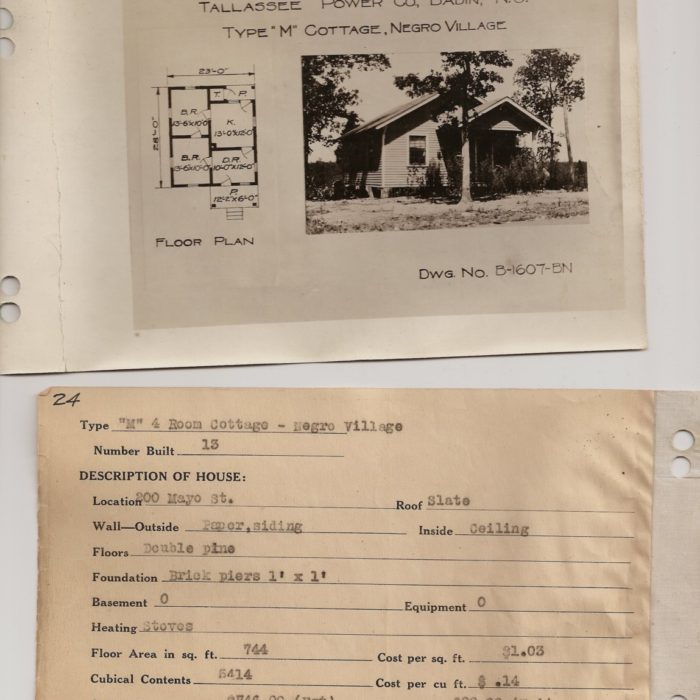

For nearly 40 years, Fickes travelled the world designing, building and reviewing the needs of industry. He witnesses the creation of several company towns, including Massena, Badin, Alcoa, Mackenzie and Moengo, where he encounters various cultures. By visiting the four corners of the world for Alcoa, Fickes is inspired by the diverse ways of doing things. He exports ideas and visions for the creation of new cities. So it is hardly surprising to find similarities between Arvida and other cities around the world which Fickes would have been inspired by. This is particularly true of the resemblance between certain houses of Arvida and the northern cottages of Rjukan, Norway.

Harry Beardslee Brainerd and Hjalmar Ejnar Skougor

Originally from New York, Harry Beardslee Brainerd was educated at the Columbia University School of Architecture and subsequently specialized in various workshops where he trained in town planning. Brainerd is known for his writings on the organization and planning of cities. He has also worked on the preparation of reports and zoning plans for several major American cities.

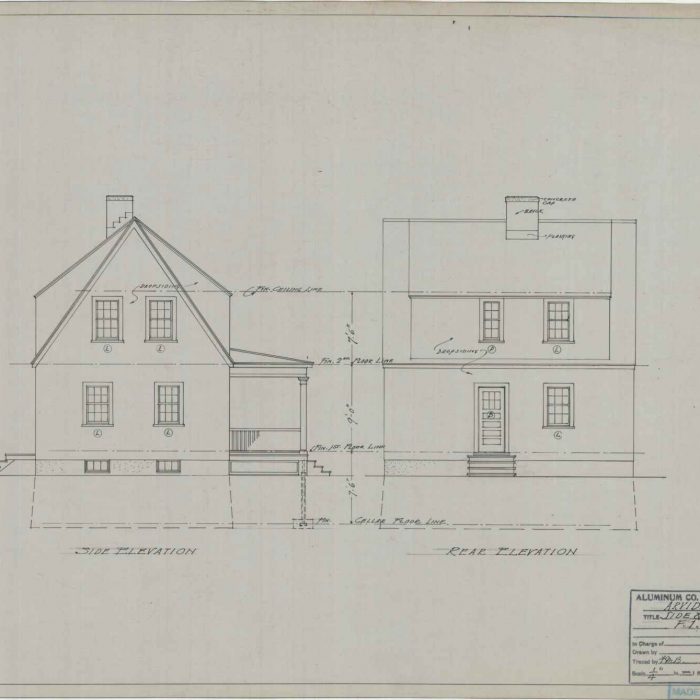

In 1924, Brainerd teams up with Hjalmar Ejnar Skougor, an industrial engineer specializing in house planning. Together, they create the plans of two new cities, Maria Elena in Chile, and Arvida. Commanded by Alcoa and drafted under the direction of its president, Arthur Vining Davis, Arvida’s plans are an original summary of urban planning, combining methods developed and tested both in America and Europe.

Harold R. Wake

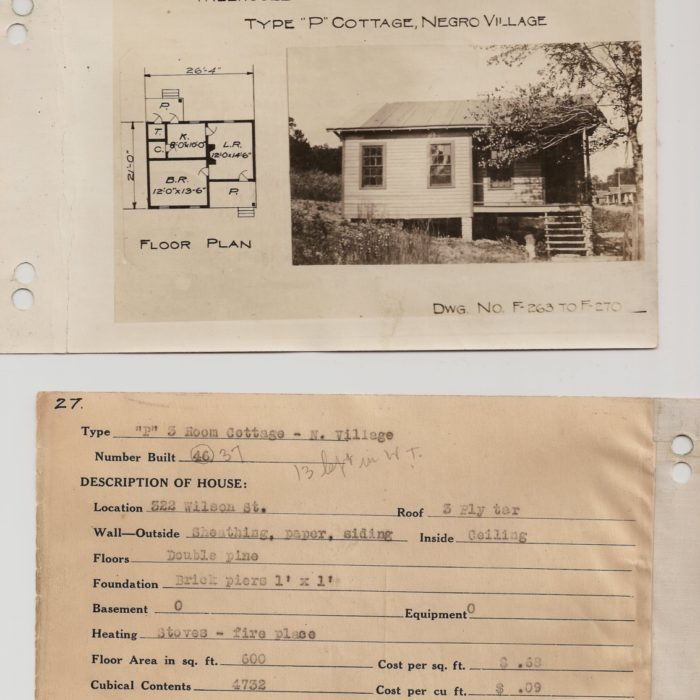

Harold R. Wake, responsible for the construction and management of the buildings in Arvida, had been with Alcoa for many years when he arrives at the Arvida construction site. A former public works engineer and head of the Alcoa real estate services in Badin, North Carolina, Wake became familiar with the problem of housing various cultures. For him, providing comfortable housing adapted to the local population will ensure a stable and productive workforce. As well, Wake controls the catalogue of houses in Badin.

When he arrives in Arvida, Wake makes some modifications to Brainerd’s plans. He eliminates most of the alleys, recognized as unwholesome places, and adds curved streets for automobile traffic. Considering the few French-Canadians compared to newcomers, Wake rejected several of Brainerd’s house designs, reworking them to make them more québécois in style. Thus, a hundred houses are adapted inside and out according to the current style of Quebec houses in order to make them compatible with French-Canadian uses and landscape. After staying more than 10 years in the city, Wake leaves Arvida to join the company’s head office in Montreal in 1937.

Alfred Lamontagne

Alfred Lamontagne was born in Lévis in 1883. Following his apprenticeship with Lorenzo Auger, he becomes an architect and settles in Chicoutimi in 1912, soon after the city fire. The only architect in the region for more than 10 years, Lamontagne benefits from the context of the period to build his reputation. The industrial expansion of the region as well as the reconstruction of part of the city allow him to sign the plans of several commercial and institutional buildings as well as large residences. After a few years of working in collaboration, Armand Gravel and Alfred Lamontagne officially join forces in 1934. In Arvida, Lamontagne draws up the plans for the Palace Theatre, the Sainte-Thérèse-de-l’Enfant-Jésus church in collaboration with Armand Gravel, as well as the presbytery of the Saint-Mathias church. The latter is the result of the work of Alfred Lamontagne, Armand Gravel and Jacques Coutu. After many accomplishments, the firm Lamontagne et Gravel closes its doors in 1961. Considered the father of Saguenay-Lac-Saint-Jean architects, Alfred Lamontagne helped to train most of the region’s architects.